City walks are more my speed. It’s the time when I remove myself from all distractions and focus solely on the steps ahead of me.

Henry David Thoreau went into the woods because he wished to live deliberately. I should think I do the same but in a city. I can embrace a kinship with the natural world. When I’m in nature, I appreciate that I am dwarfed by trees and outnumbered by animals who see me when I cannot see them. It puts us clumsy humans in our rightful place.

But city walks are more my speed. It’s the time when I remove myself from all distractions and focus solely on the steps ahead of me. And this is no small challenge: Reports show that, on average, Americans check their phones 344 times a day—roughly every four minutes.

I used to run for exercise, but the onset of middle age sidelined me from that. It’s for the best, really. Walking is more meditative. But I have grown to rely on this almost daily outlet. For me, walking is part exercise, part exorcism: Stretching my legs casts out my demons.

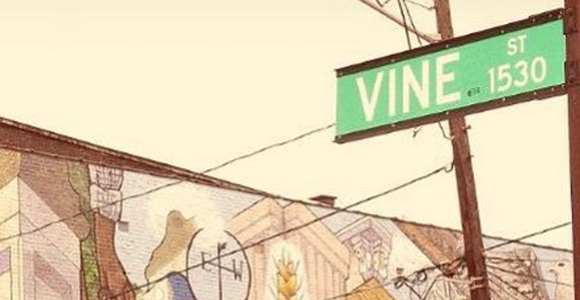

Having spent a couple of decades working in Over-the-Rhine (OTR), walking the busy streets and formidable stairways is where I feel most at home. I slip in my AirPods and climb the Main Street steps up to Mt. Auburn’s Jackson Hill Park. Or the Reading Road steps to Prospect Hill, with its rows of Italianate houses too beautiful to miss in spring. I may attempt Sycamore’s endless northern incline or Pendleton’s narrow cobblestone avenues. I rarely have a plan where I’m going. For me, that’s how it should be.

The steady sounds of honking cars and police sirens are, for this journeyman, preferred over the chatter of birds in a dense wood. I like to see faces I don’t recognize as well as the ones that I do—street poets and artists, bartenders and shop owners—who have outlasted recessions and riots because this is their home. Their roots are generational. Though I am a transient of sorts, my heart tells me I’m home, too.

It’s not always a love letter. On my walks I’ve seen discarded needles, shell casings, poverty, and police overreach, but I realized long ago that, in witnessing human struggle, I am attesting to its inherent dignity. When I look at the city from a safer perch, I miss the individual brushstrokes that make up the entire work of art. Thus, I do my part to be in the thick of it.

After Timothy Thomas was killed in 2001, riots followed. OTR was on lockdown for days. At the start of the unrest, we were escorted to our cars by SWAT, and, in truth, I couldn’t wait to get out. After a few days, I couldn’t wait to come back. As the years progressed and federal funds funneled into the neighborhood, OTR got a facelift. Now it’s become a trendy place to eat, drink, and shop.

I love that the neighborhood is still intact—that most of its businesses have weathered the worst of COVID-19 and the economic hardships that followed. But I will always seek out the less gentrified spots of OTR, areas that haven’t been gutted and polished. Maybe this bruised but beautiful neighborhood is the place where I feel most present, most alive in my own skin. Maybe this is where I live most deliberately.

Christopher Heffron, a 1997 graduate of the Mount with majors in English and Communications, was editor of Dateline. He is Editorial Director of Franciscan Media.